Author Archive

Several years ago Forbes magazine staged a playoff bracket among 32 corporate jargon “abominable expressions” to determine the most annoying one. Each day two expressions were matched against each other and Forbes readers voted on the phrase that advanced in the playoff bracket. Some strong contenders made the playoffs: core competency, burning platform, open…

The email arrived from a major retailer advising us to “order by tomorrow to gift your valentine.” Here we have another noun (gift) turned into a verb. We looked it up in multiple dictionaries and found, lo and behold, it is grammatically correct. But we judge it sonically wrong. In writing, and speaking, certain…

Every writer’s desk should have a dictionary on it. Clearly, we all know about the online word lookup function of the computer or the word of the day app. But, for the writer, nothing replaces the serendipity of discovery that goes along with the actual handling of a book where words are compiled. Writers…

We are often asked by those who sometimes have a little fear or intimidation regarding the written word about a good way to get started when we just have to produce something. Our preference is to engage freewriting, a method that tends to clear the mind and capture focus, albeit in a roundabout way. …

Some of the most common mistakes in writing and editing involve selection of the right word when we have the choice of similar words. And, as we continue to emphasize, getting it right in writing is important because a knowledgeable reader or listener makes judgments about us based on how we present. From time…

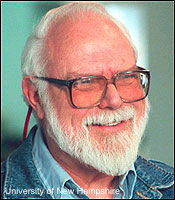

In the world of print journalism one of the icons of effective writing was the late Don Murray, a Pulitzer Prize winner, Boston Globe writer, an editor for Time, and author of more than a dozen books. Murray believed everyone had the capacity to write with power and clarity. One of the key elements is…

Several years ago Forbes magazine staged a playoff bracket among 32 corporate jargon “abominable expressions” to determine the most annoying one. Each day two expressions were matched against each other and Forbes readers voted on the phrase that advanced in the playoff bracket. Some strong contenders made the playoffs: core competency, burning platform, open…

The email arrived from a major retailer advising us to “order by tomorrow to gift your valentine.” Here we have another noun (gift) turned into a verb. We looked it up in multiple dictionaries and found, lo and behold, it is grammatically correct. But we judge it sonically wrong. In writing, and speaking, certain…

Every writer’s desk should have a dictionary on it. Clearly, we all know about the online word lookup function of the computer or the word of the day app. But, for the writer, nothing replaces the serendipity of discovery that goes along with the actual handling of a book where words are compiled. Writers…

We are often asked by those who sometimes have a little fear or intimidation regarding the written word about a good way to get started when we just have to produce something. Our preference is to engage freewriting, a method that tends to clear the mind and capture focus, albeit in a roundabout way. …

Some of the most common mistakes in writing and editing involve selection of the right word when we have the choice of similar words. And, as we continue to emphasize, getting it right in writing is important because a knowledgeable reader or listener makes judgments about us based on how we present. From time…

In the world of print journalism one of the icons of effective writing was the late Don Murray, a Pulitzer Prize winner, Boston Globe writer, an editor for Time, and author of more than a dozen books. Murray believed everyone had the capacity to write with power and clarity. One of the key elements is…